Laboratory diagnostics

Pathological diagnostics

Pathological diagnosis plays a decisive role in neuroendocrine tumors (NET). It is carried out at the Institute of Pathology in accordance with the WHO guidelines (current WHO classification of neuroendocrine neoplasias of the gastroenteropancreatic system from 2022) and the ENETS. The Institute of Pathology at the UKGM, Marburg site, is involved in six organ tumor centers and has many years of expertise in the field of NET. The methods available include conventional histology and cytology, intraoperative frozen section diagnostics, immunohistochemistry (> 10,000 immunohistochemical stains per year on three immunostaining machines) with the use of all common neuroendocrine markers, molecular pathology and electron microscopy.

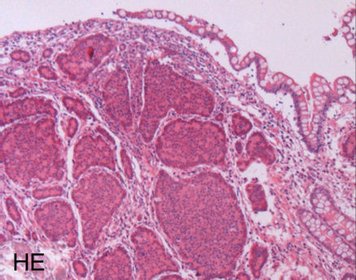

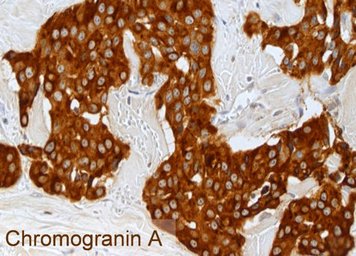

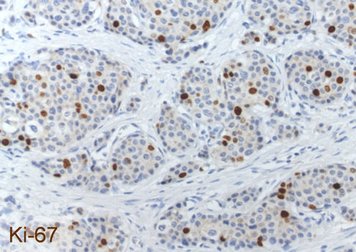

Each NET is routinely examined for the neuroendocrine basic markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin as well as for the proliferation marker Ki-67 by immunohistochemistry. The images show a well-differentiated NET G2 of the ileum with the typical histology (HE = microscopic image in hematoxylin-eosin staining), a strong cytoplasmic staining of the tumor cells for chromogranin A and a labeling of 12% of the tumor cell nuclei for Ki-67. The detection of chromogranin A and/or synaptophysin proves the presence of a NET. The proliferation marker Ki-67 is the basis for tumor grading and is of outstanding prognostic significance. The pathologist must therefore make this parameter available to the clinician for further treatment planning.

Laboratory values in the form of blood or urine tests are used in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasia for various purposes:

Confirmation of the diagnosis, progression parameters, determination of concomitant diseases that play a role in the selection of therapy ( e.g. renal insufficiency), monitoring of therapy side effects ( e.g. blood count changes), prognosis assessment.

The so-called tumor markers in NEN can be divided into general markers, which are elevated in most patients, and specific markers, which detect a specific hormone syndrome, for example.

The most important general tumor marker in NEN is chromogranin A. This marker is often elevated in patients with hormone syndromes, but also in patients with functionally inactive tumors, and can then be used as a progression parameter. Extremely high values reflect a high tumor burden and therefore a less favourable prognosis. The same detection method should always be used for the determination, as the values can vary when different assays are used and are not comparable. In addition, other possible errors (e.g. increased values in chronic atrophic gastritis, when taking gastric acid blockers, etc.) must be taken into account.

Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is also a general serum marker in NEN, although its determination is mainly useful in poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas, in which chromogranin A is often negative.

Another general marker that is elevated in approx. 80% of patients with pancreatic NEN and approx. 50% of patients with small bowel NEN is pancreatic polypeptide. As it can be elevated in many other diseases (e.g. diarrhea of other causes), it is preferably used as a follow-up parameter when chromogranin A is not elevated.

The most important specific markers that detect a certain hormone syndrome have already been mentioned in the explanation of the syndromes and are only briefly summarized here:

Serotonin is the lead hormone in carcinoid syndrome. In cases of carcinoid syndrome, it is useful to determine the degradation product of serotonin, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIES), in acidified 24-hour urine.

(Pro-)insulin and C-peptide are the marker hormones of insulinoma. They are determined closely together with the blood glucose level as part of a so-called starvation test to detect (or rule out) an insulinoma.

Gastrin is the lead hormone in gastrinoma syndrome or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. If the serum fasting level is only slightly elevated (<1000pg/ml), a lectretin test was previously recommended. In this case, an increase in gastrin levels of at least 200pg/ml after administration of secretin is considered diagnostic confirmation. However, secretin is often not available, so that the clear recommendation to carry out this test has been dropped in the latest guideline of the European Society ENETS and the diagnosis of gastrinoma is made taking into account the typical symptoms, the gastrin value and imaging.

The determination of plasma glucagon is useful for confirming the rare glucagonoma syndrome, and the determination of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) is useful if a VIPoma syndrome or Verner-Morrison syndrome is suspected.

In summary, meaningful laboratory diagnostics therefore depend on the specific situation of the patient. Typical tumor markers are usually chromogranin A as a general marker and, if necessary, the specific marker hormone.

Endoscopy:

In our modern interdisciplinary endoscopy department, we offer the complete spectrum of endoscopic diagnostics of the gastrointestinal tract (gastroscopy, colonoscopy, endosonography, capsule endoscopy, push and pull enteroscopy of the small intestine, ERCP). Modern, high-performance endosonography equipment is available for endoscopic ultrasound diagnostics including punctures.

Nuclear medicine procedure in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasia

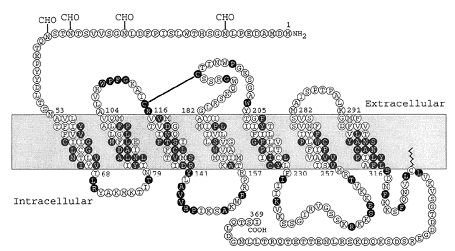

Neuroendocrine neoplasias (NEN) are characterized by the frequent presence of the so-called somatostatin receptor, in addition to other, sometimes very specific characteristics. This receptor, which is found on the cell surface, is a prerequisite for somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS). Since the mid-1990s, SRS has been available as a particularly suitable examination method. A low-level radioactive substance (usually octreoscan) is injected into the arm vein and after an exposure time of 4 to 24 hours, this substance attaches itself to the cells of the neuroendocrine tumor. It docks onto the receptor for somatostatin (SMS) shown below.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS)

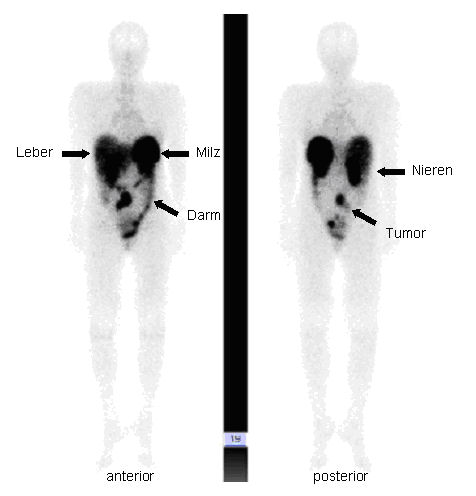

After an exposure time of 4 or 24 hours, images of the entire body are taken from the front (anterior) and back (posterior) using a so-called gamma camera. The exposure time in the gamma camera shown (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) is approx. 1.5 hours spread over several sections.

The image data collected in this way can be represented as follows: the contour of a human body with intensive storage of radioactivity (black) in the area of the liver, spleen, kidneys and intestines can be seen. In the example shown, the pathological change is the storage in the middle of the abdomen, which corresponds to a neuroendocrine tumor of the small intestine.

With the help of this procedure, all neuroendocrine tumor sites can be specifically visualized, i.e. it is an important instrument for finding a primary focus of a neuroendocrine neoplasia, but also all possible metastases (secondary tumors); always assuming that this tumor also has the somatostatin receptor.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

A more recent development in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors is positron emission tomography (PET), in which whole-body examinations are also carried out using radioactive substances. In addition to the possibility of examining the known somatostatin receptor (e.g. 68Gallium-DOTATOC/DOTATATE-PET), there is another possibility. With the help of the metabolism of the various hormones that convert neuroendocrine cells, the substance DOPA with the radioactive fluorine atom 18F is able to be specifically absorbed into these cells so that three-dimensional images of the body can be taken from the outside using the PET-CT device shown below. Poorly differentiated NEN such as NEC have an increased glucose metabolism and can therefore be easily visualized using FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose).